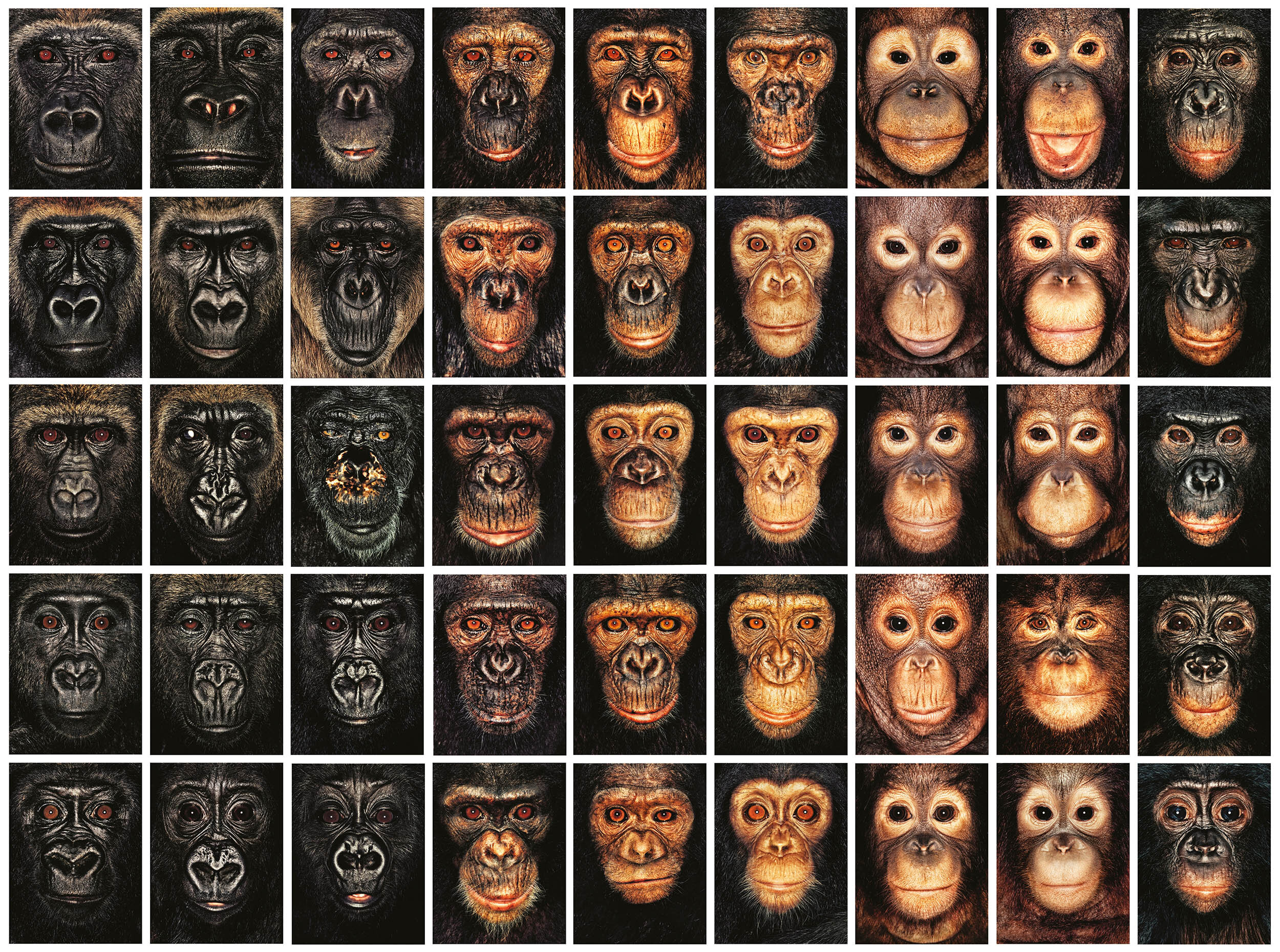

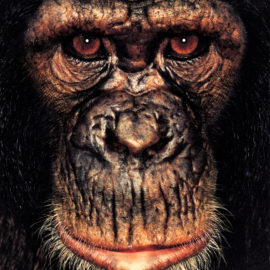

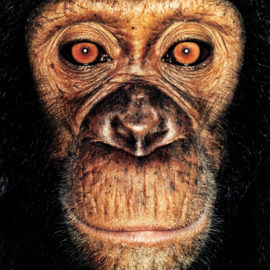

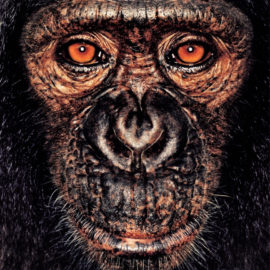

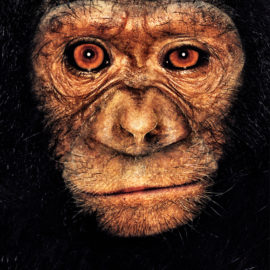

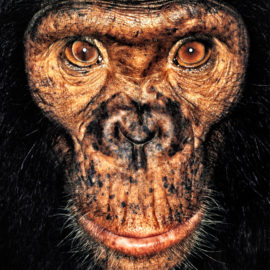

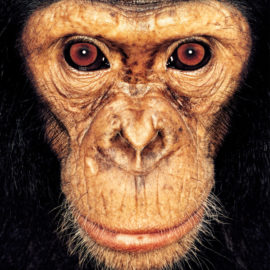

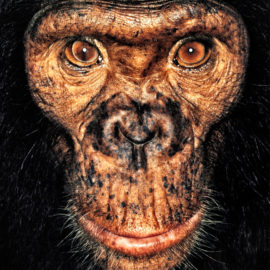

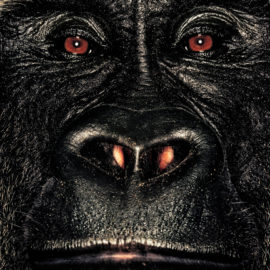

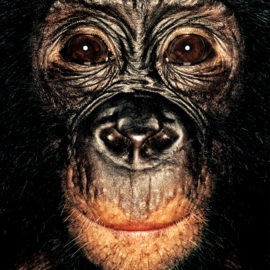

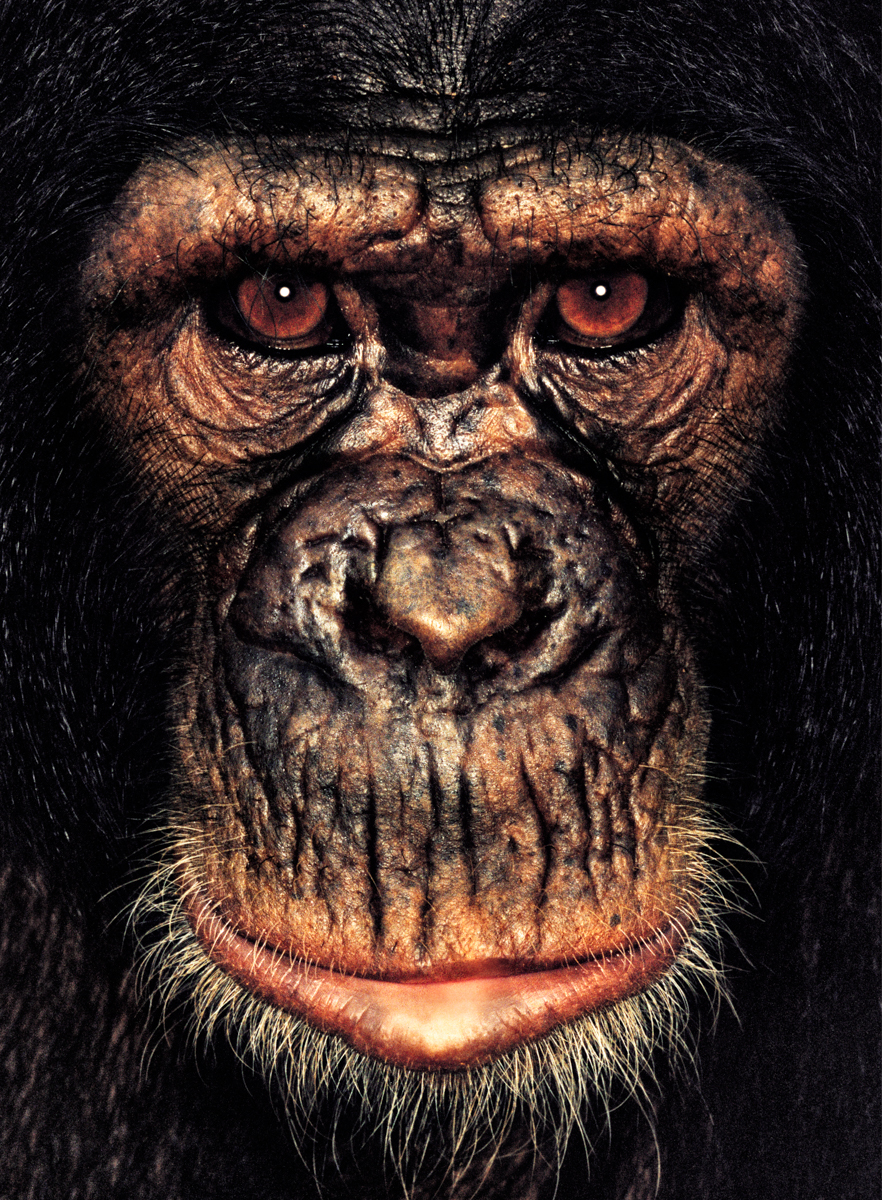

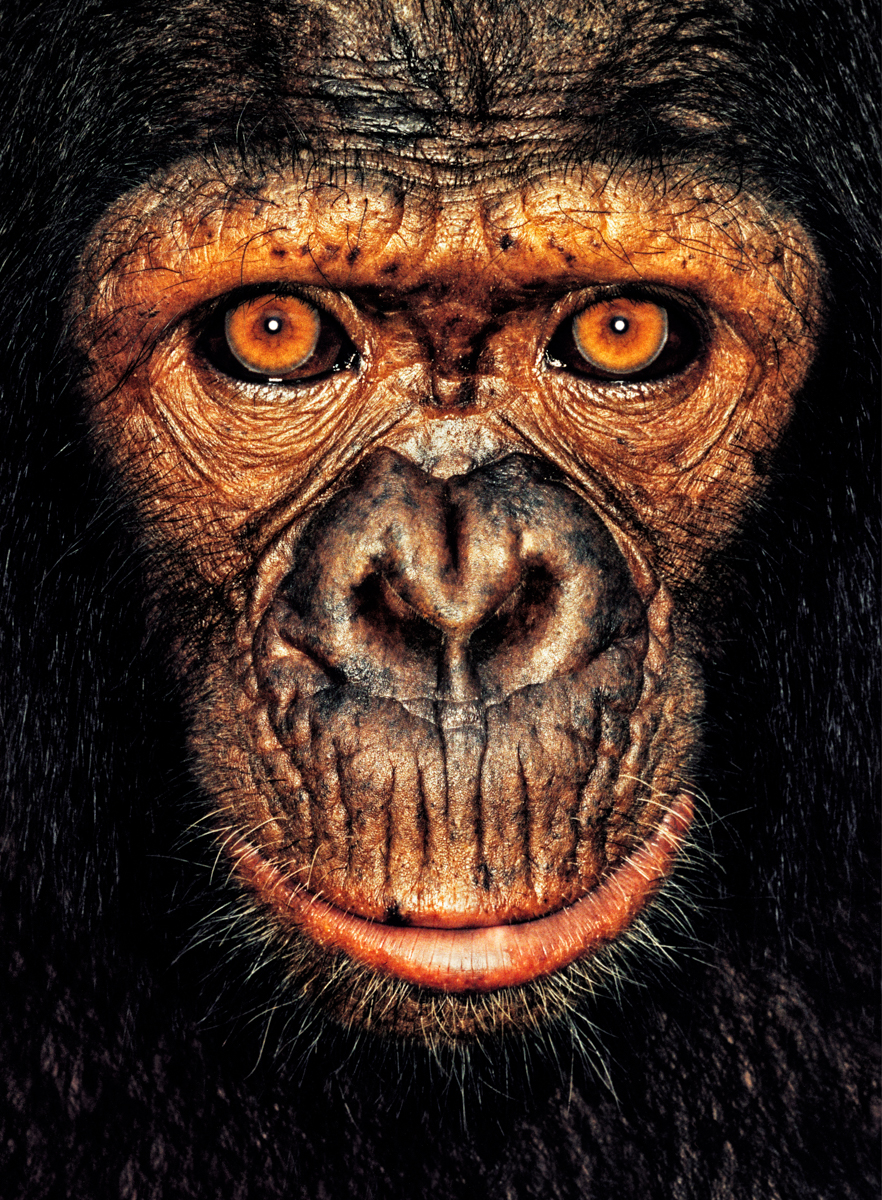

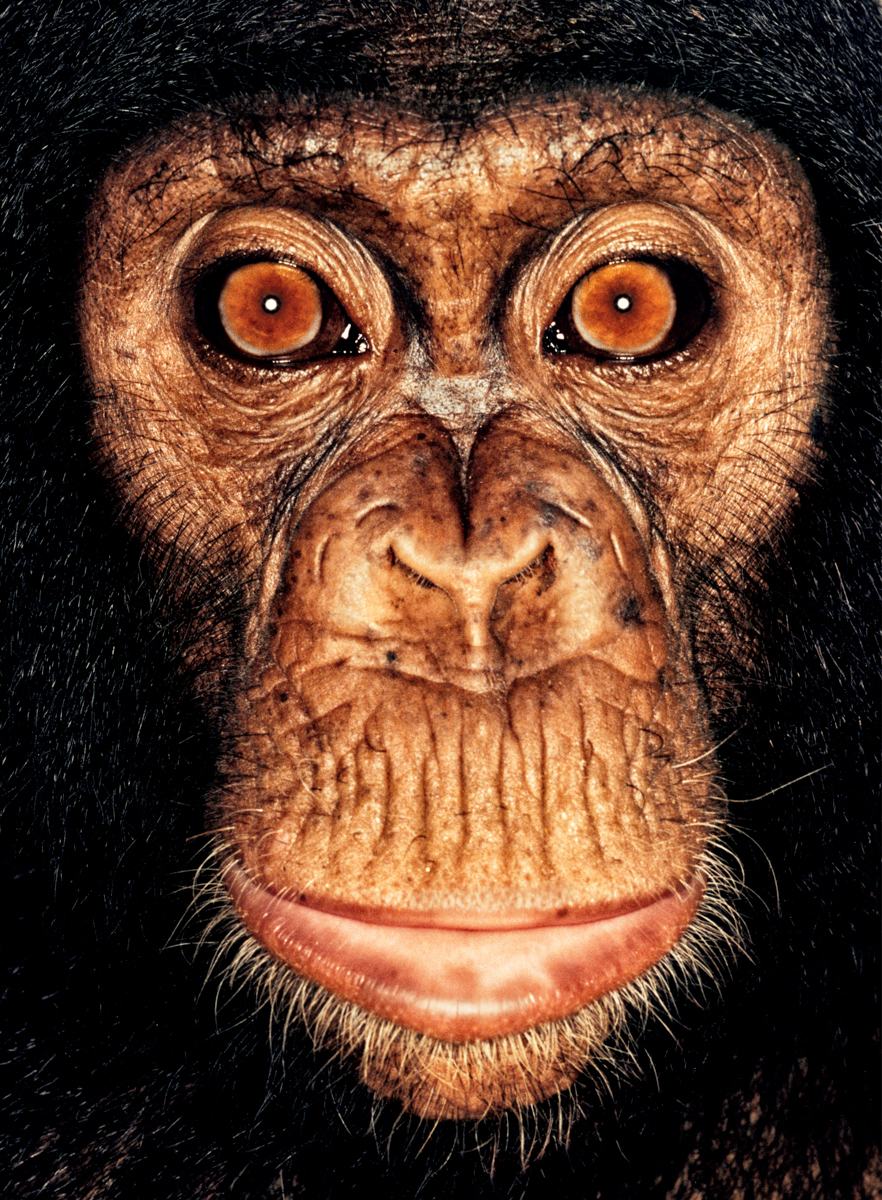

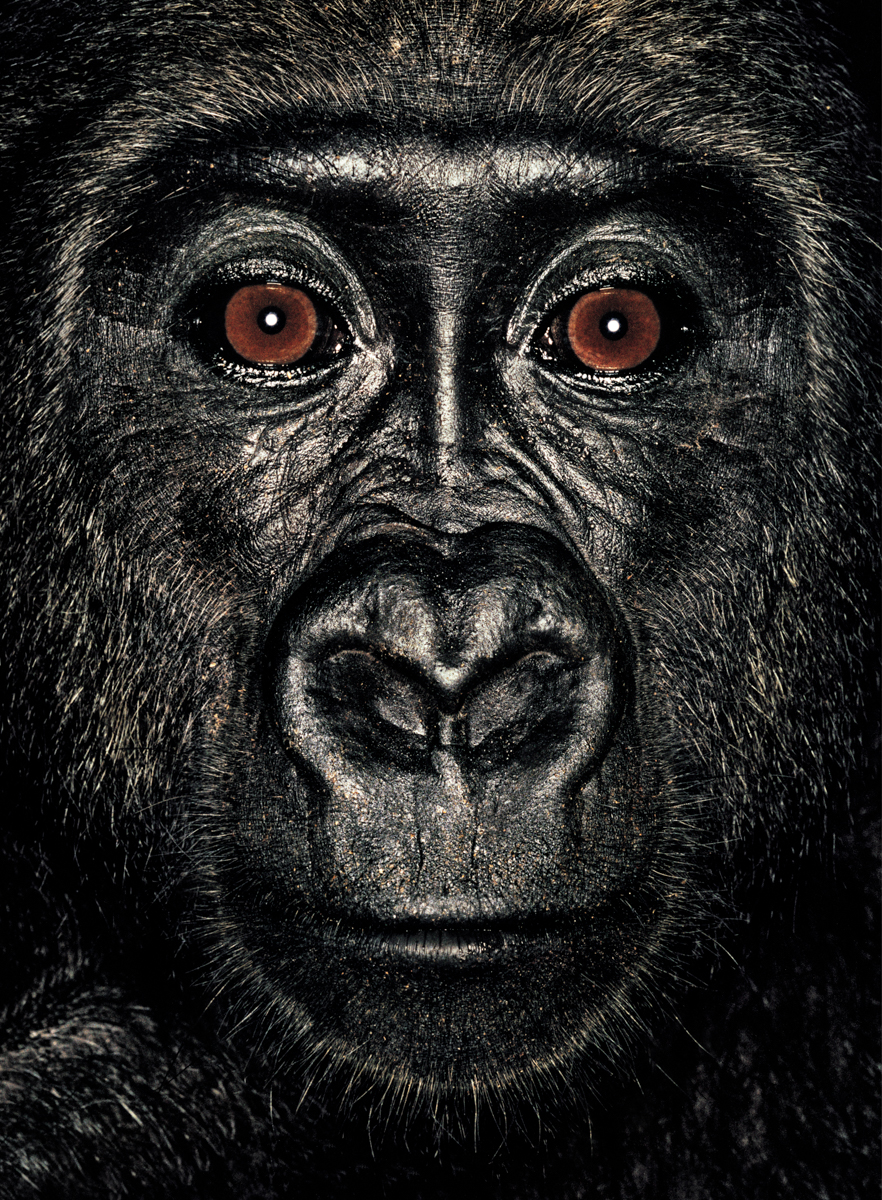

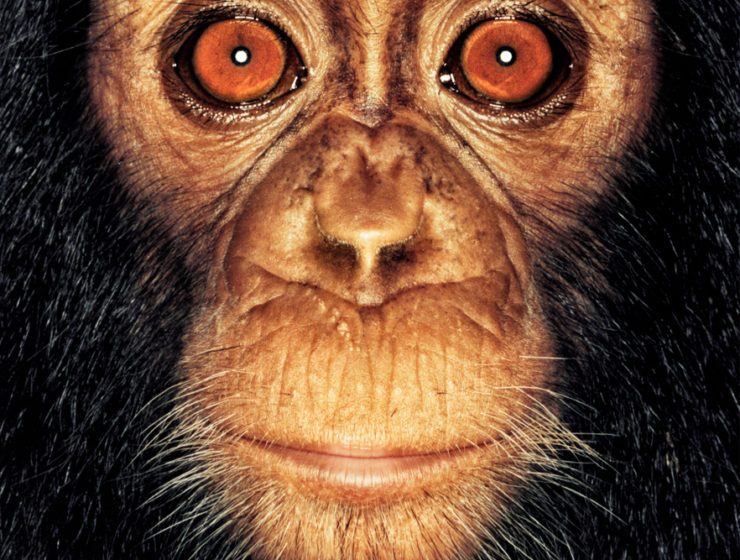

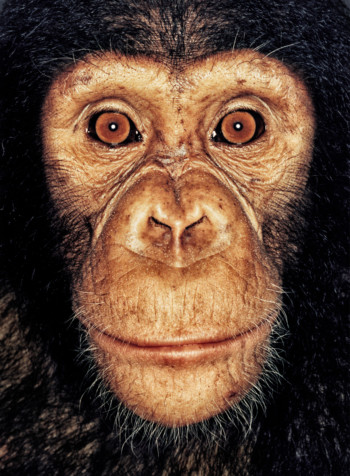

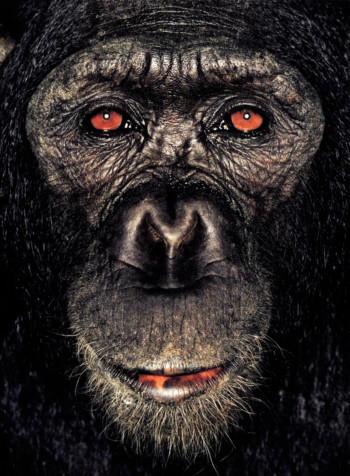

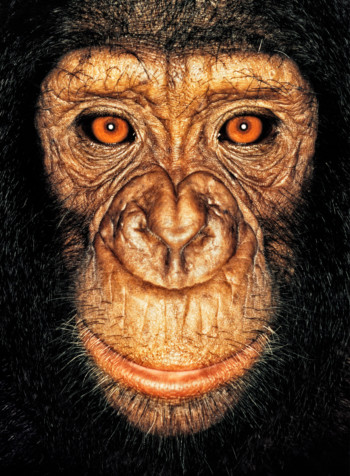

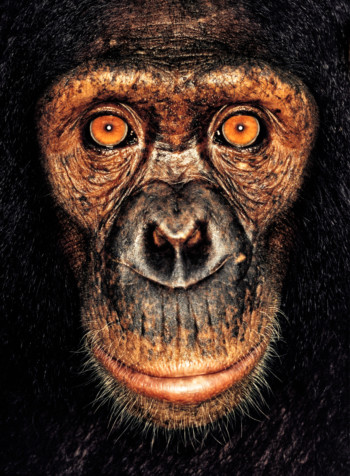

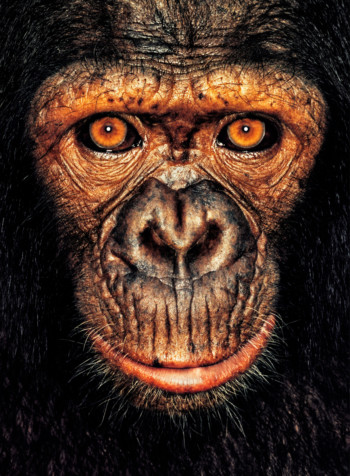

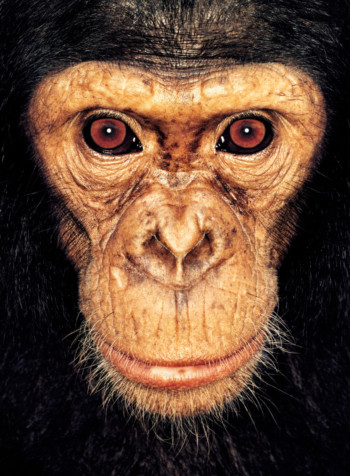

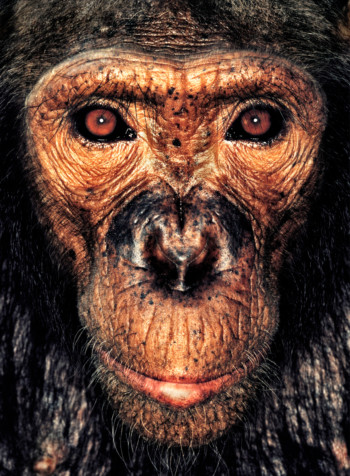

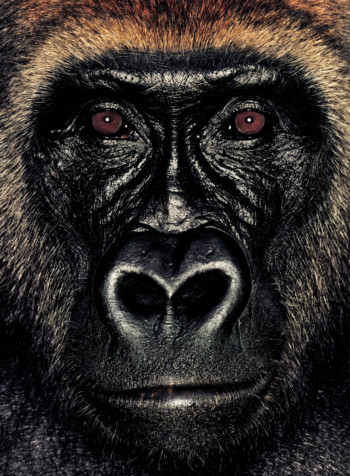

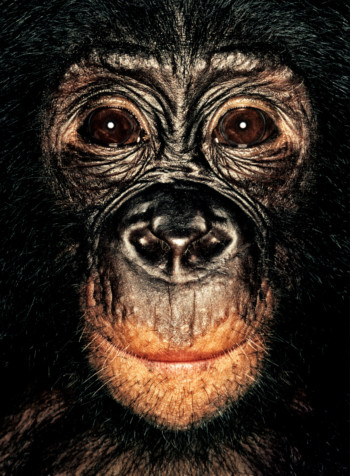

How would you describe the presence of the gorillas?

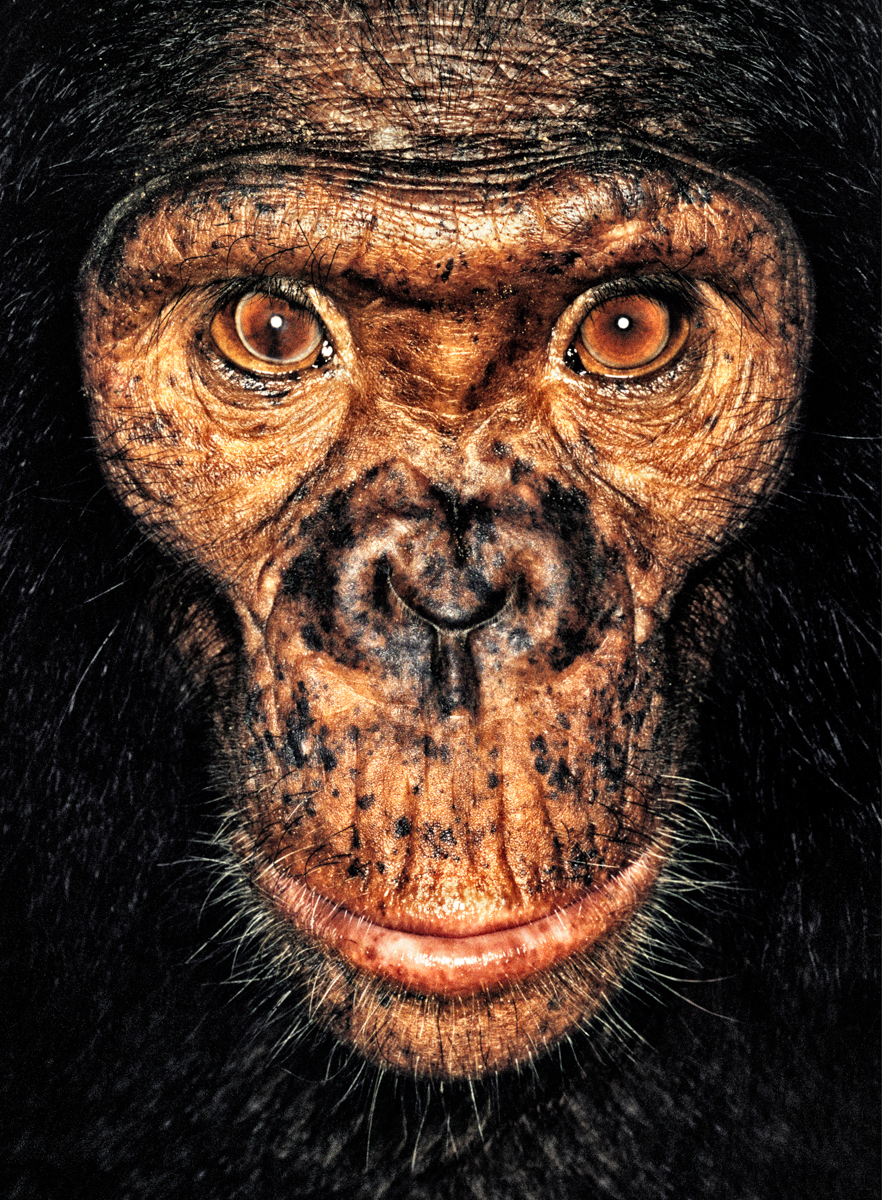

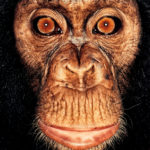

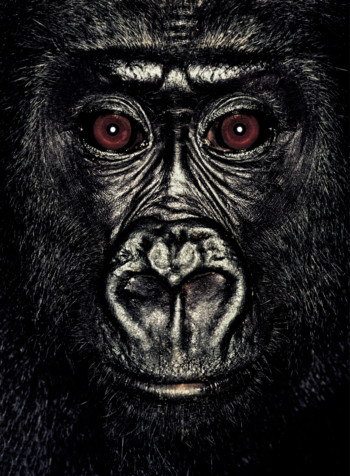

I could remember looking at their faces and just thinking how similar they are to us. We think of them as different species. But they each have their own individual traits and characters, which are very familiarly human.

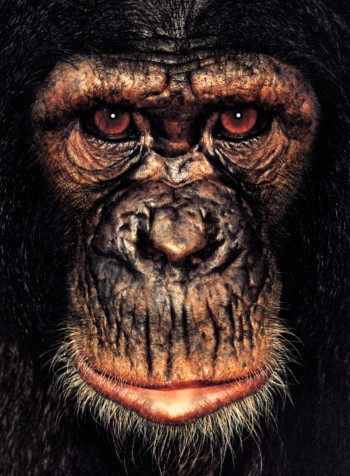

Genetically, they are very similar to us. We are different from a lot of animals, But the great apes ask us questions about ourselves, because they are so close to us. They are the grey space between man and animal.

How did you begin this project?

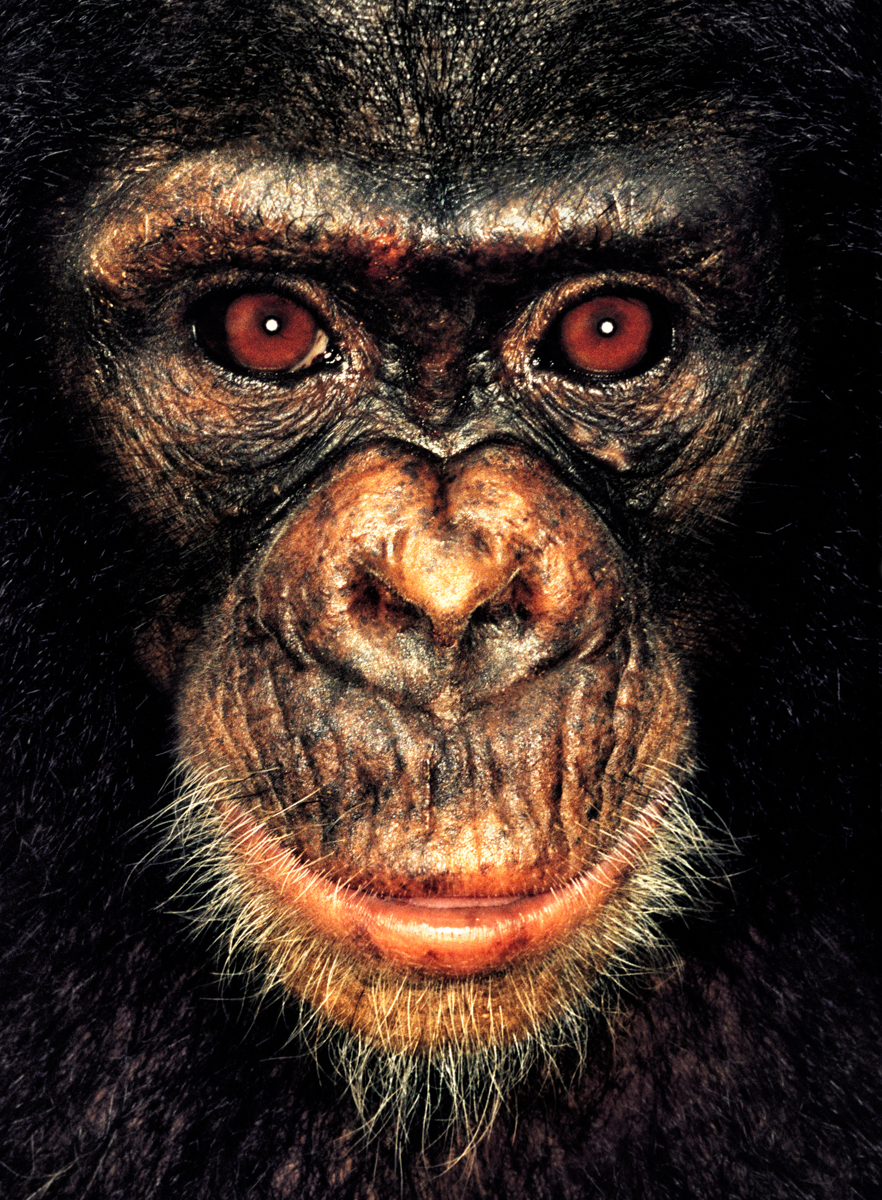

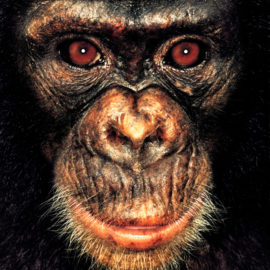

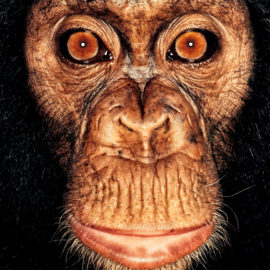

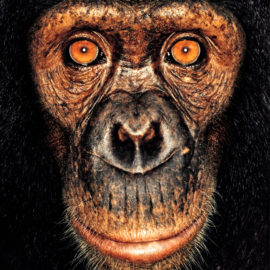

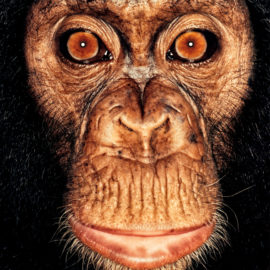

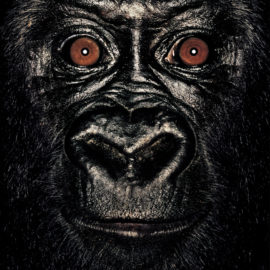

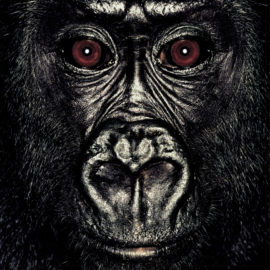

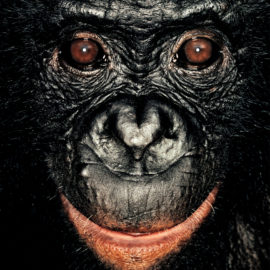

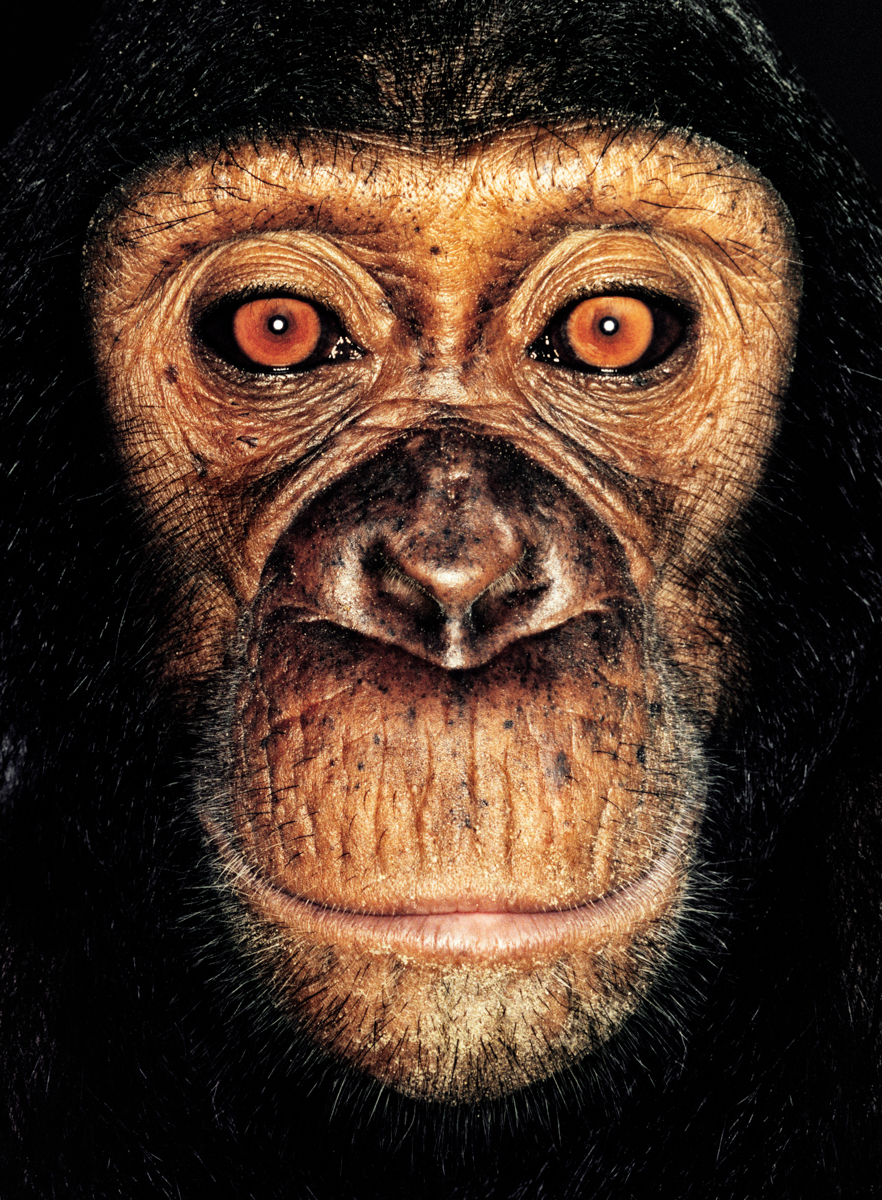

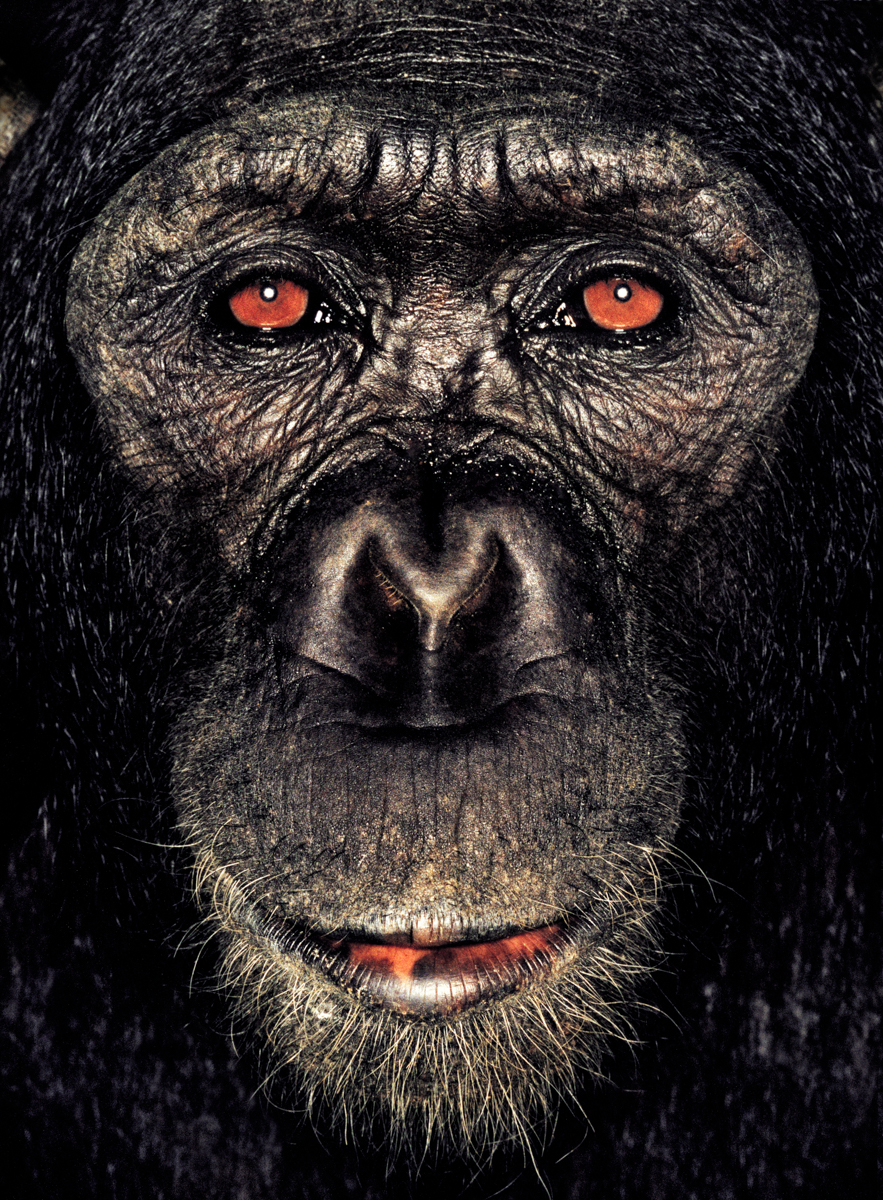

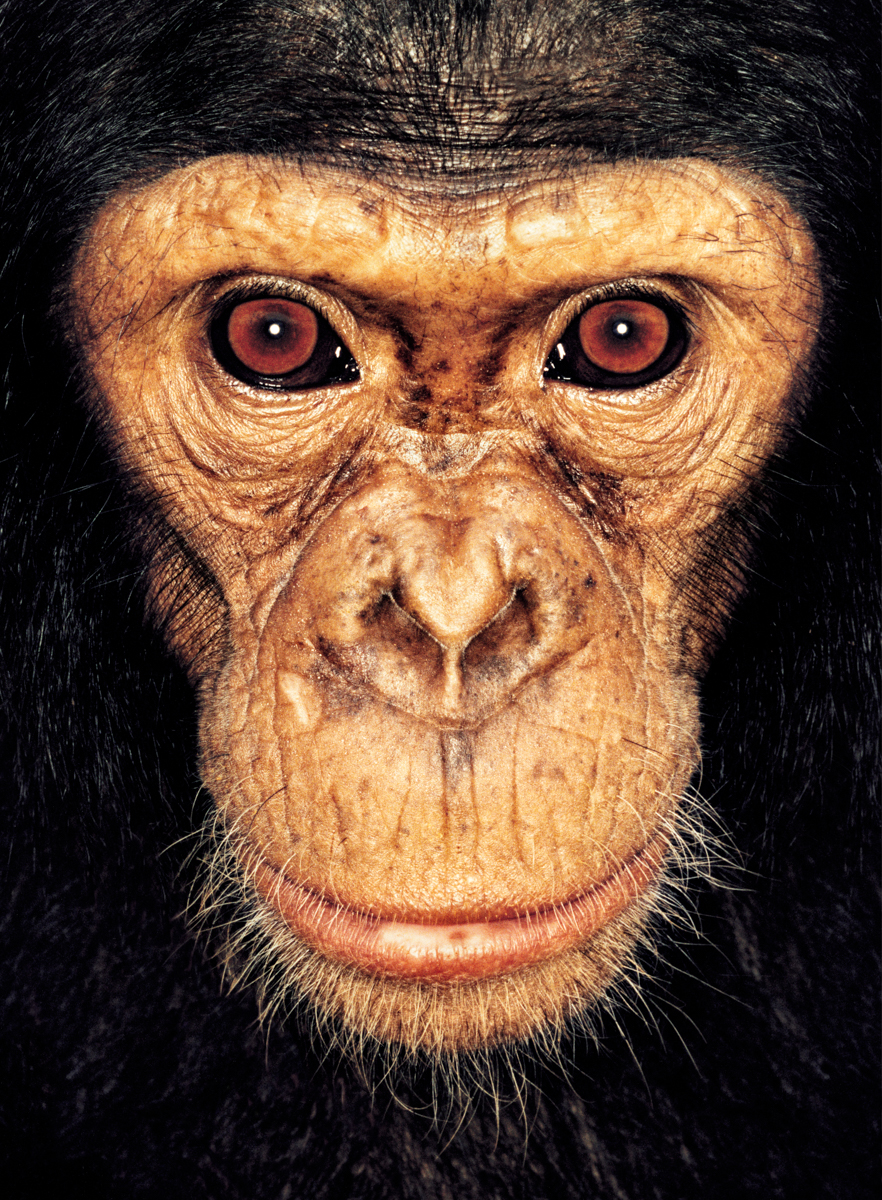

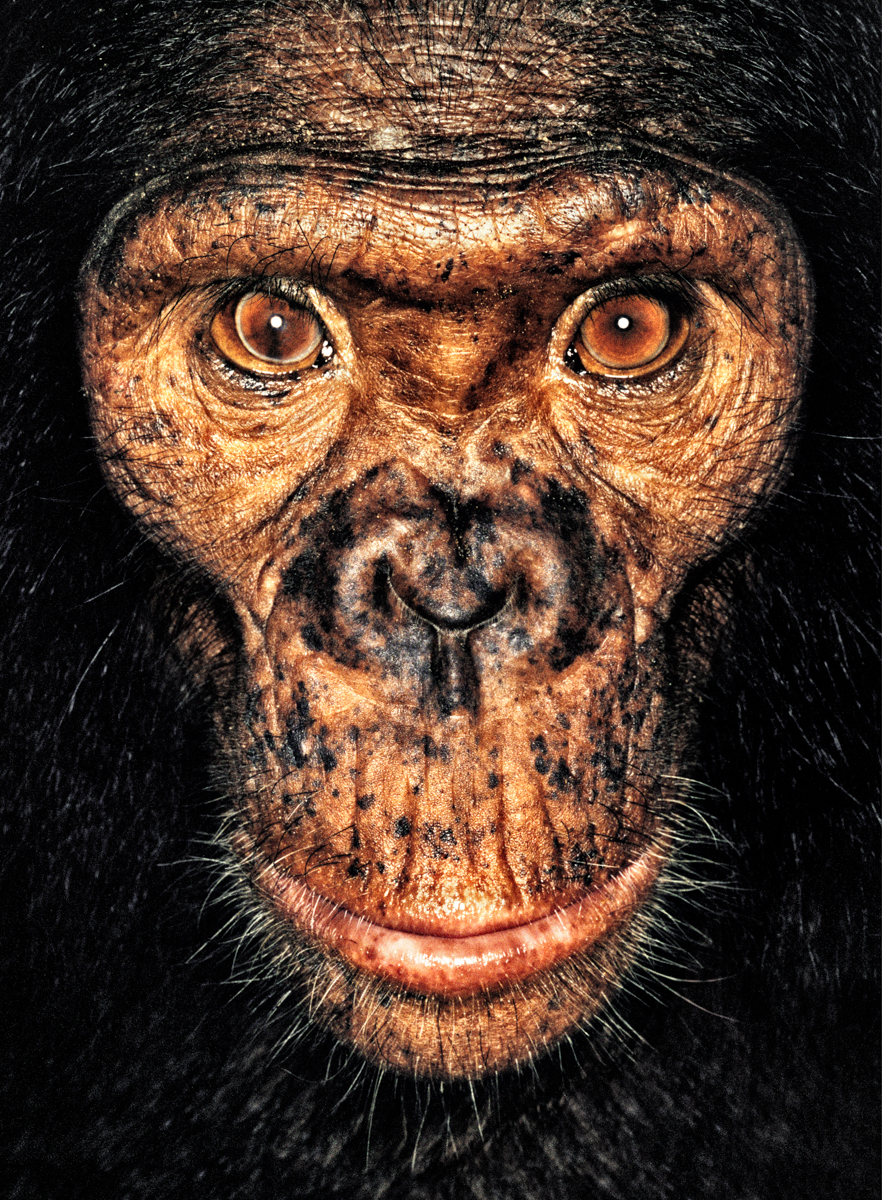

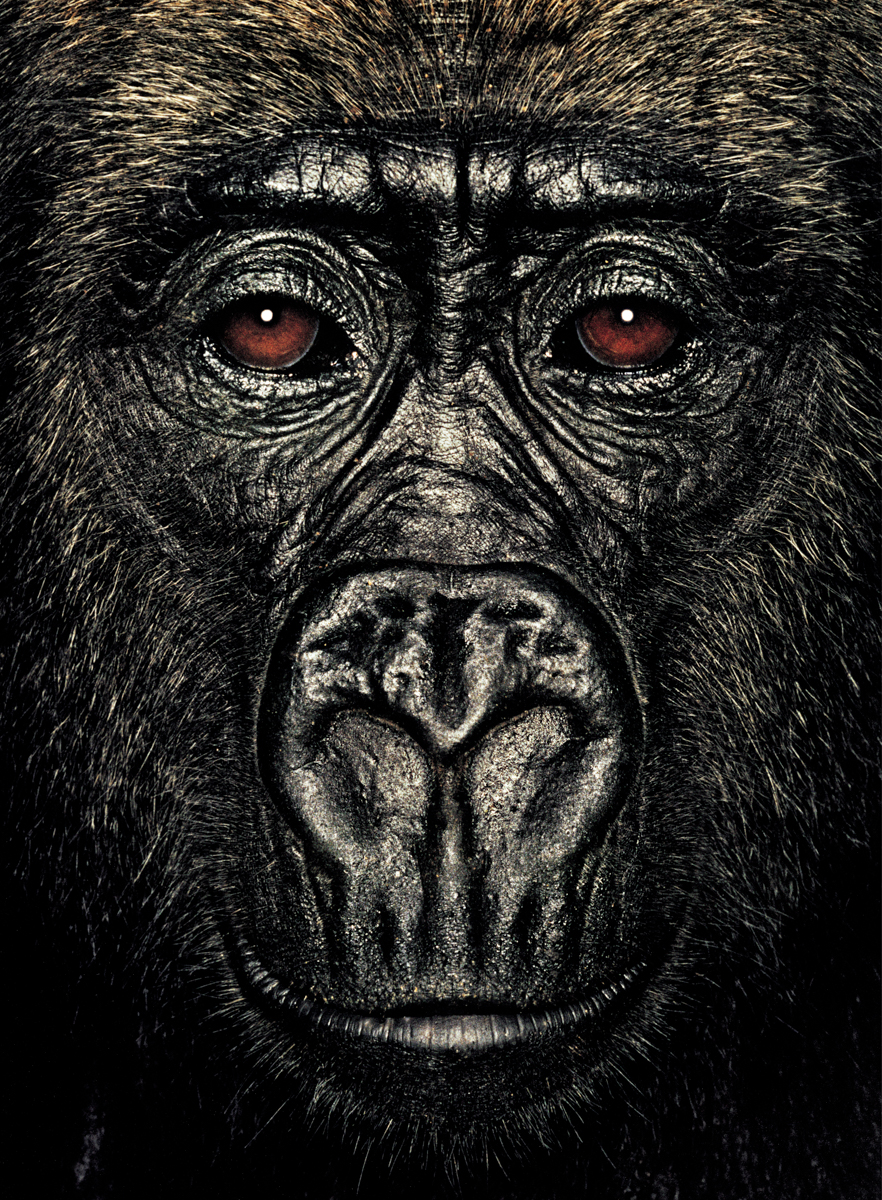

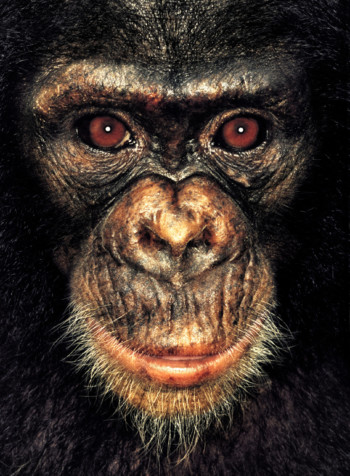

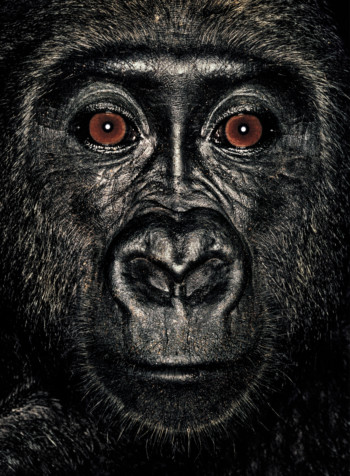

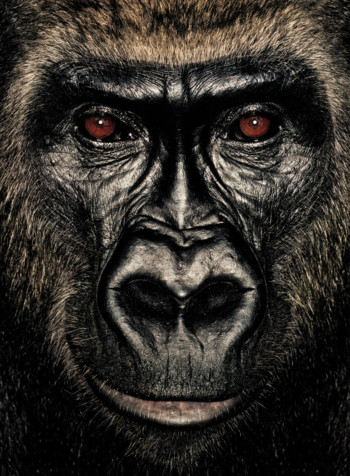

I had begun to wonder if I could try and take passport photographs of apes. I didn’t want to do something with a long lens. I wanted to kind of be in with them, to be close.

One of the first places I wrote to was Monkey World, which is an ape rescue centre in Dorset. I asked if I could make some portraits of the apes there. And I actually got a really negative, hostile letter back from them saying what I wanted to do was cruel.

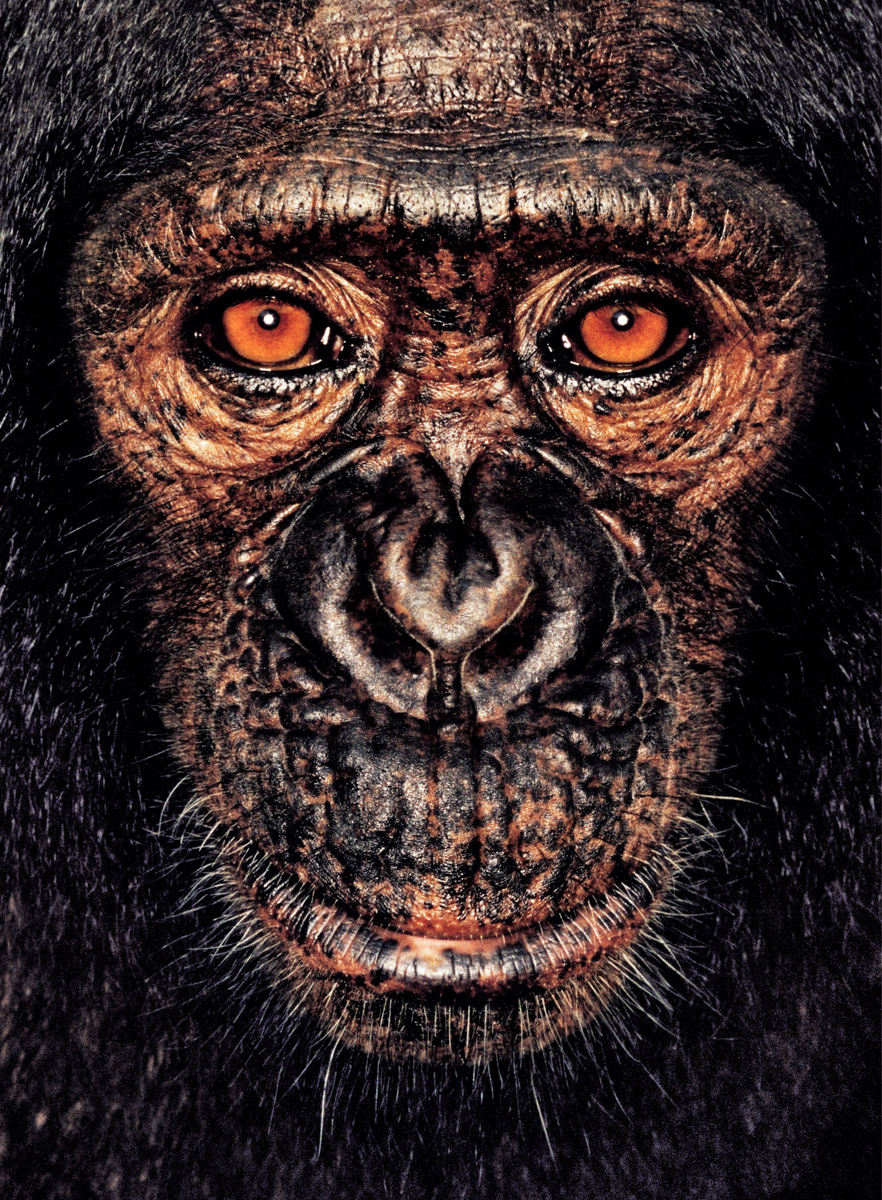

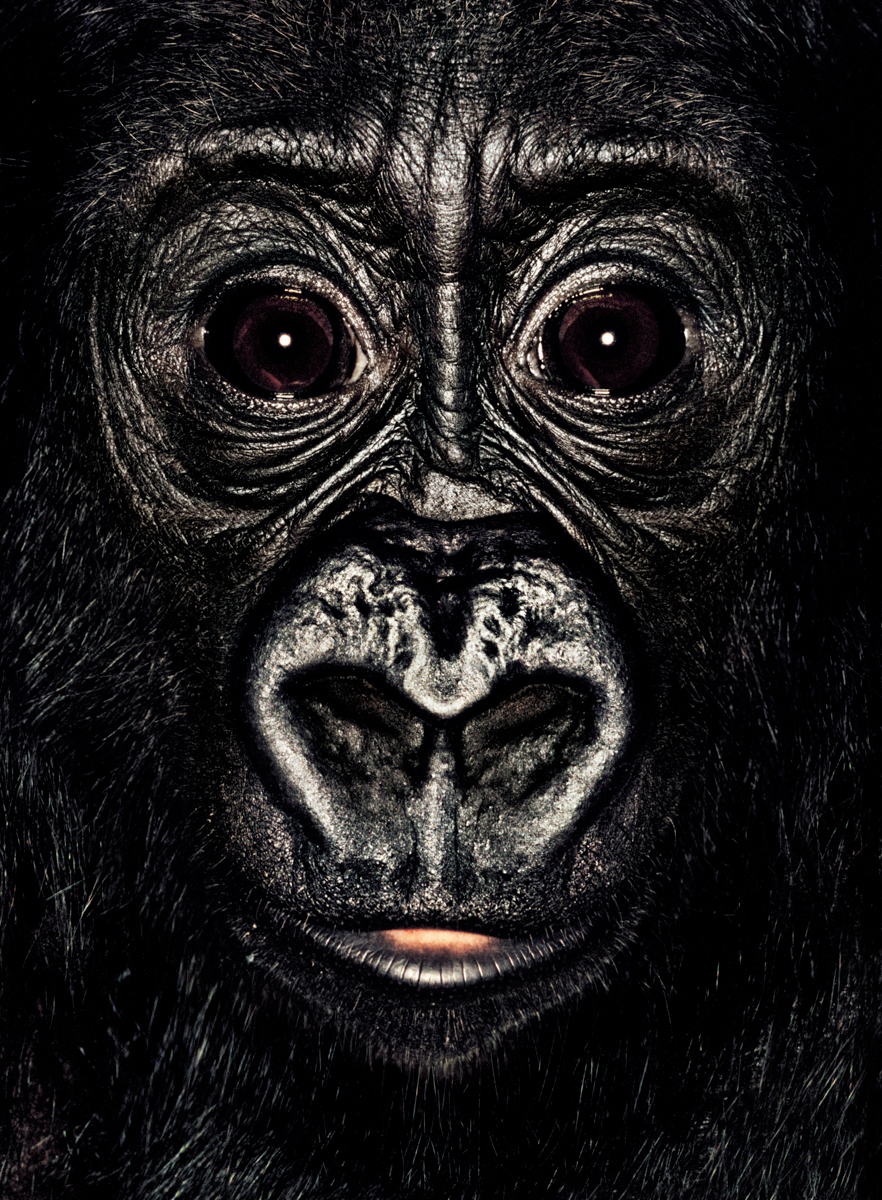

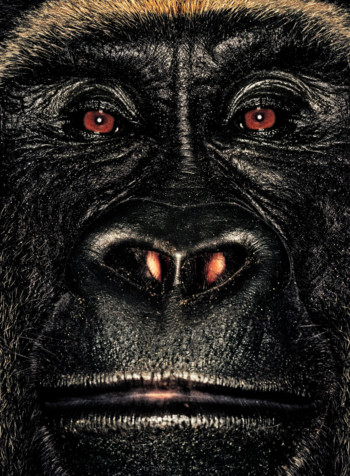

I really hesitated at that point. But I contacted a Berlin zoo and received a letter saying they had a young gorilla who had to be raised by humans, because his mother had rejected him. They welcomed me to take a picture of him. Taking that picture showed me how fast and how chaotic the moment of taking pictures is.

But I got this portrait of him. It was the last frame of the film. The picture was closer than the others, even more cropped than a passport picture. But it was very direct. The gorilla was looking right through the lens. It seemed like the gorilla was looking right at me, almost into me.

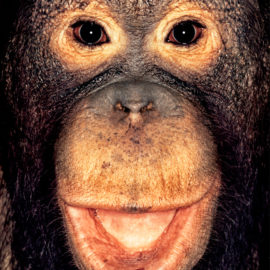

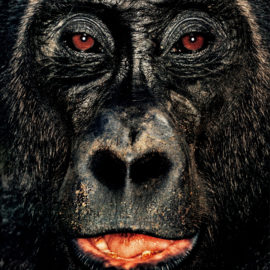

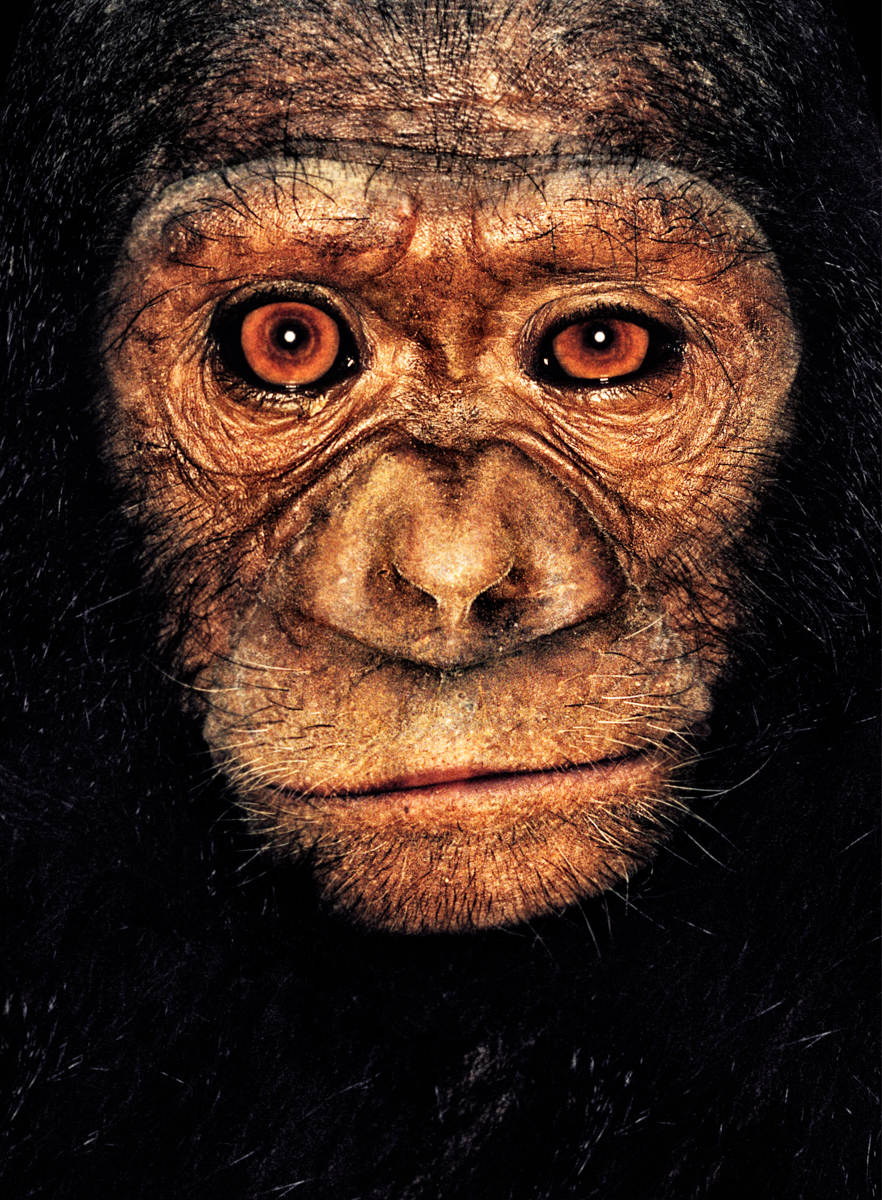

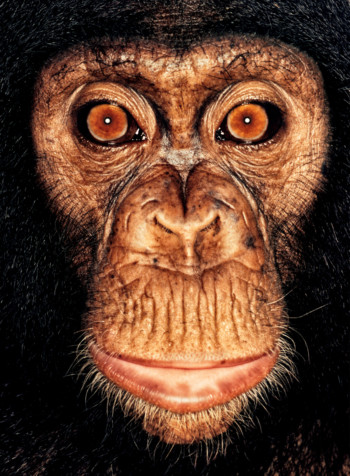

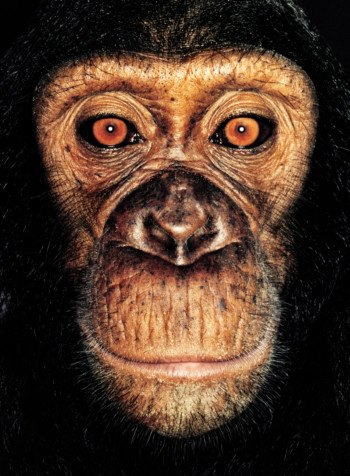

Many of the apes you photograph are quite young. How did that change the project?

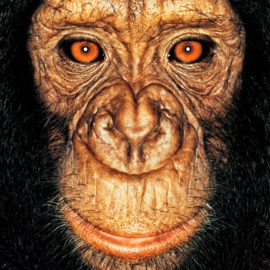

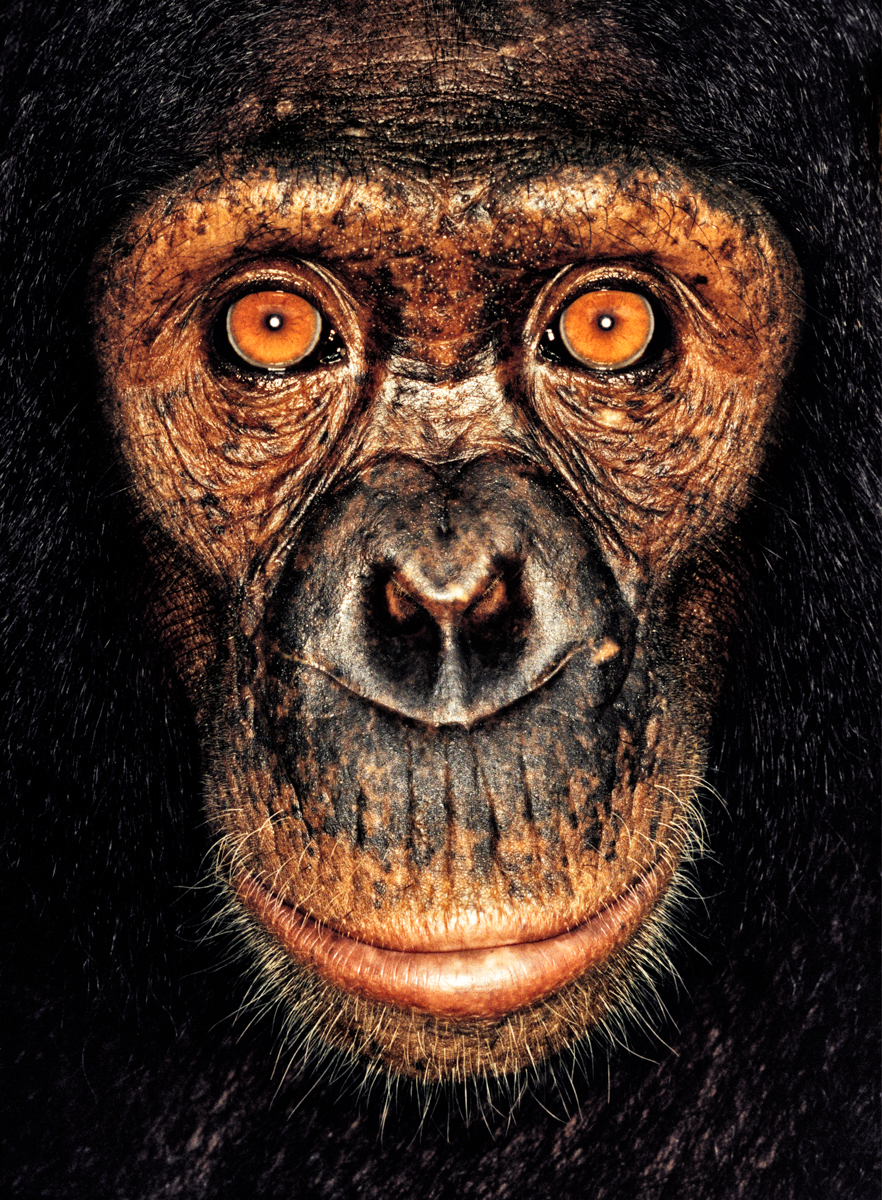

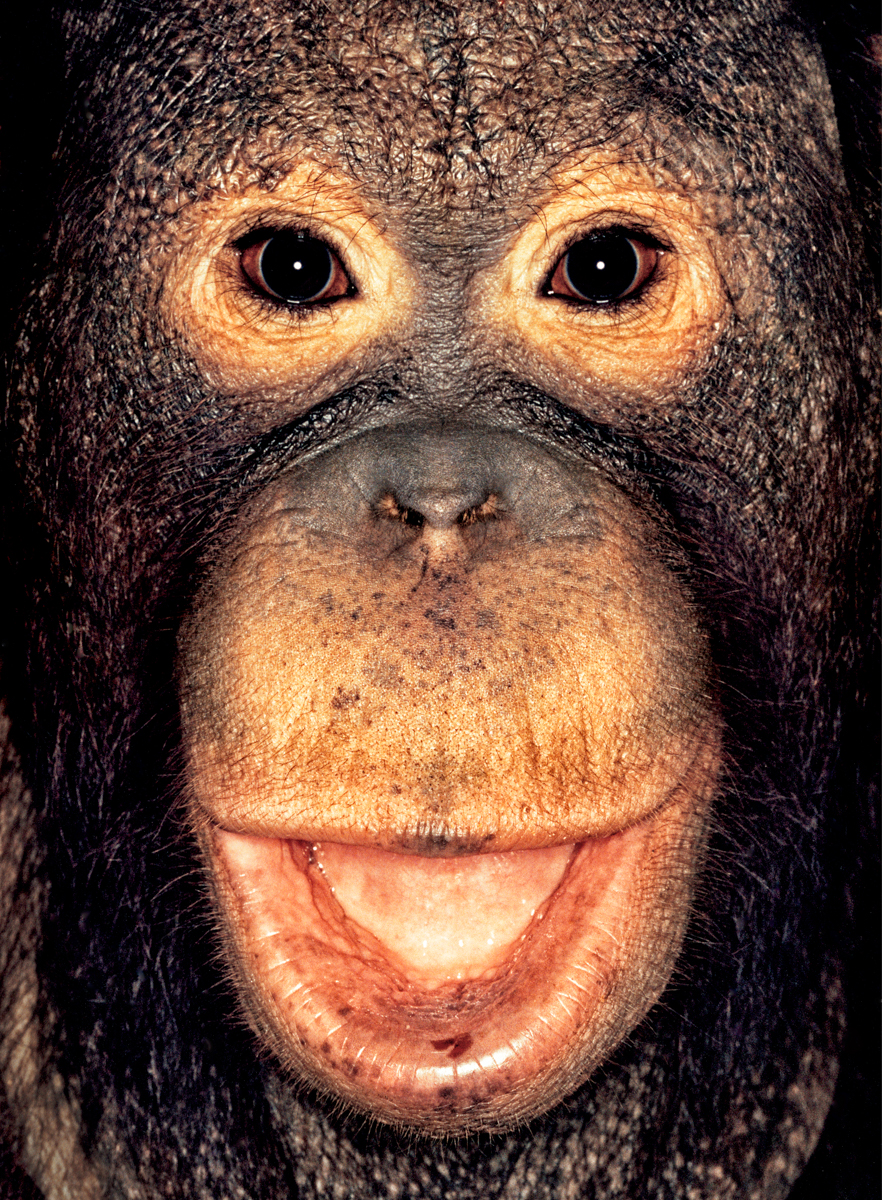

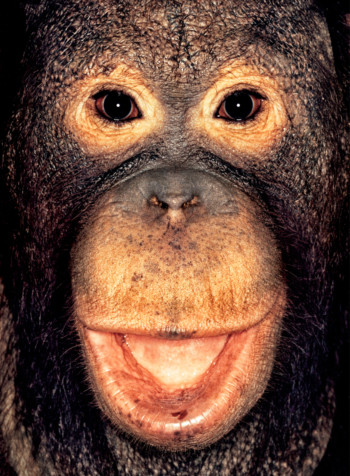

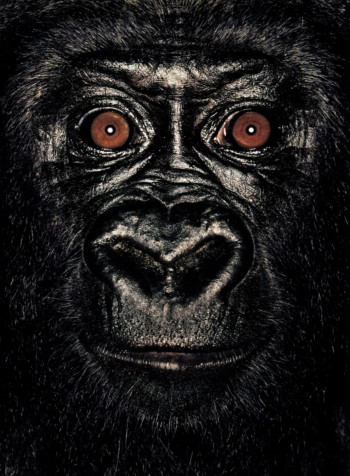

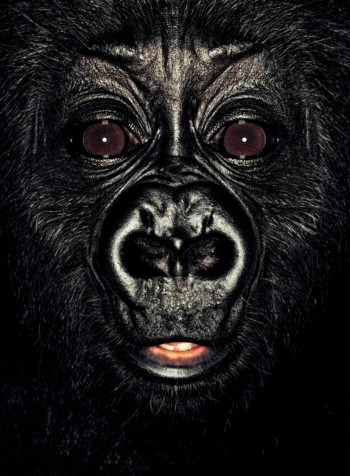

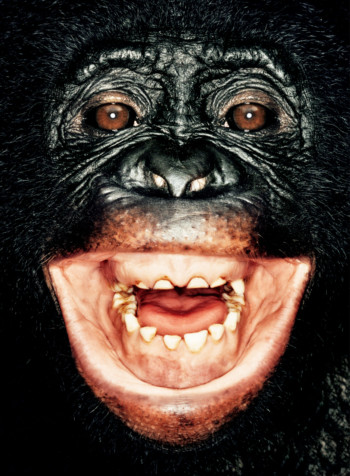

It took me back to my childhood. There’s a naughtiness to young apes that took me back to some of the memories I had of being a young boy.

I remember trying to take a picture of one ape, and finding another one trying to tie my shoelaces. They would rummage through my pockets and take anything I had in there. I loved it actually; being around these gorillas who just loved being young.

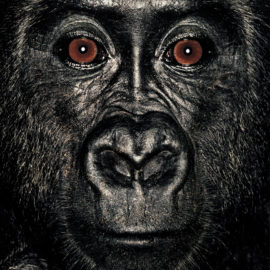

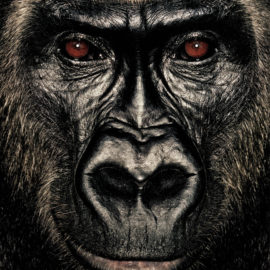

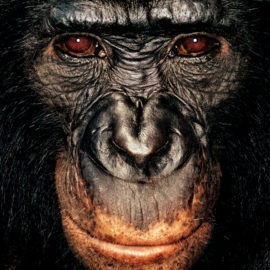

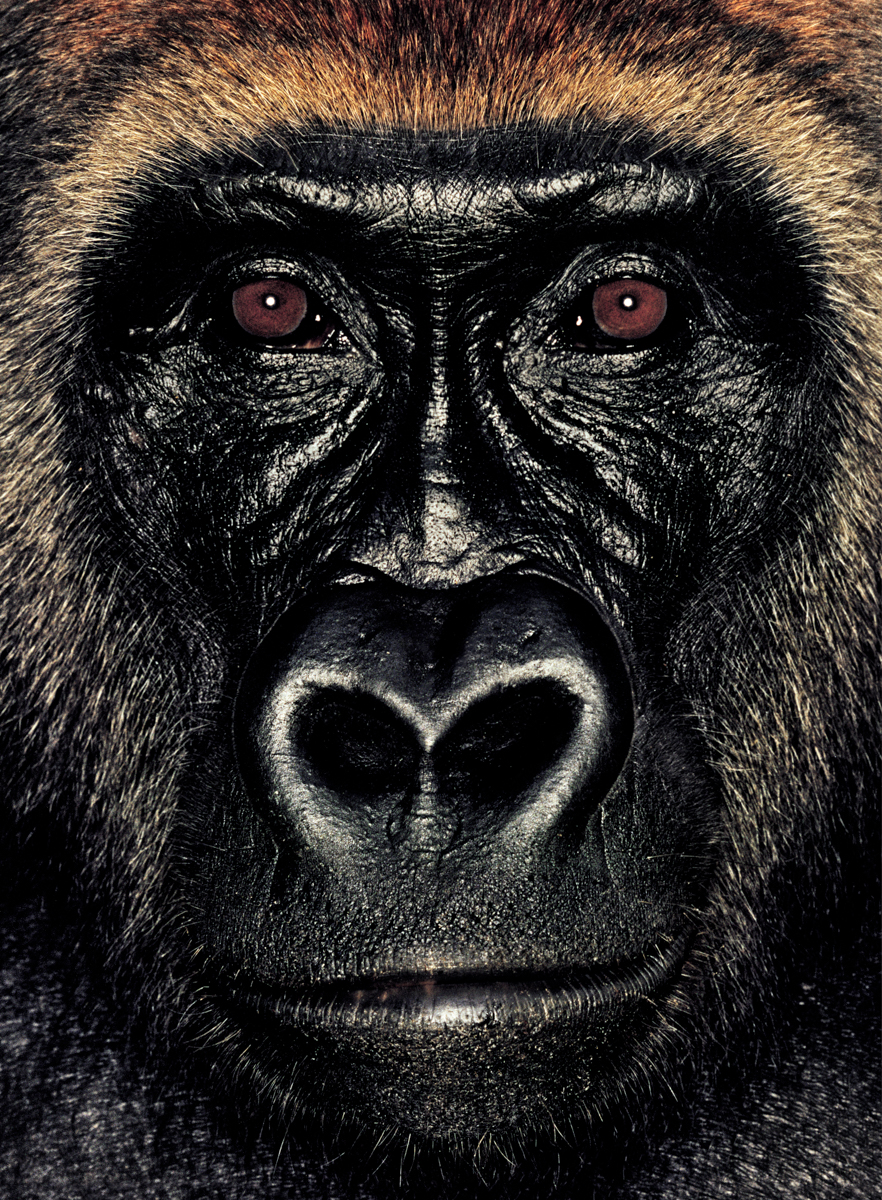

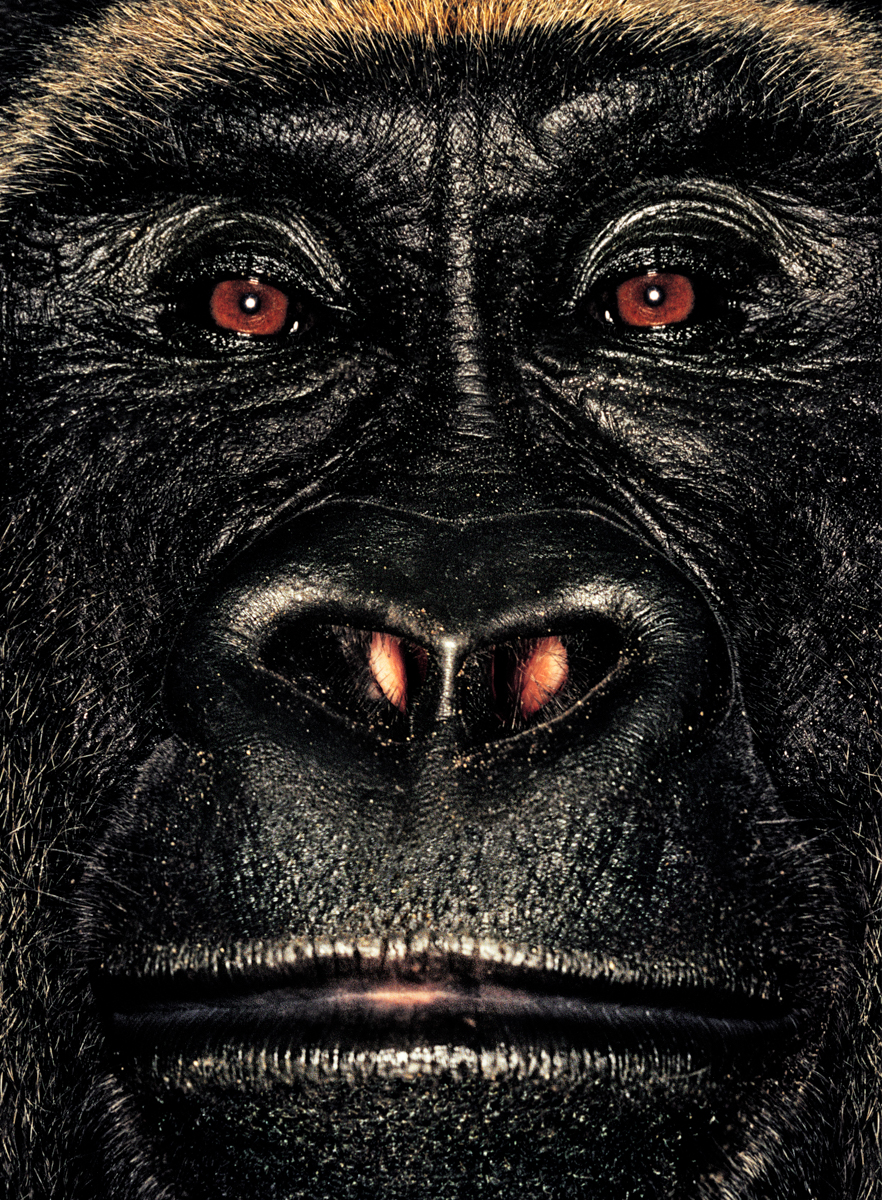

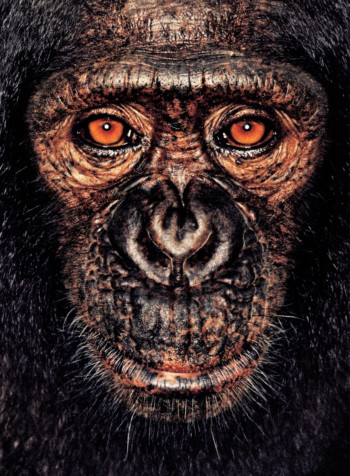

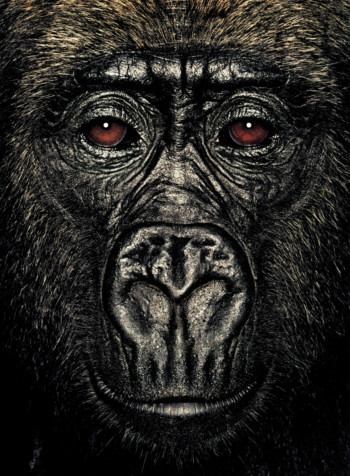

Many ape species are critically endangered around the world, did that inform the project?

Yes, I wanted the work to help us think about that relationship between man and animal.

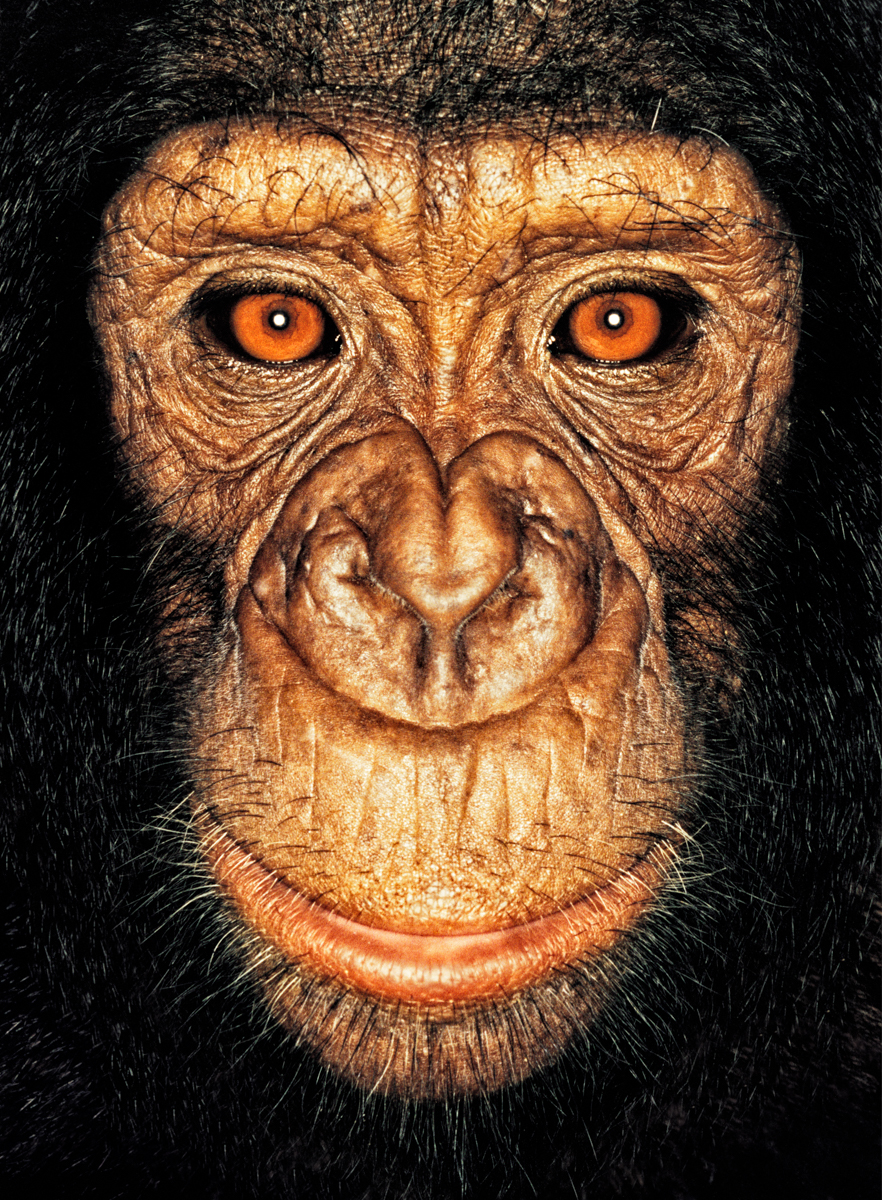

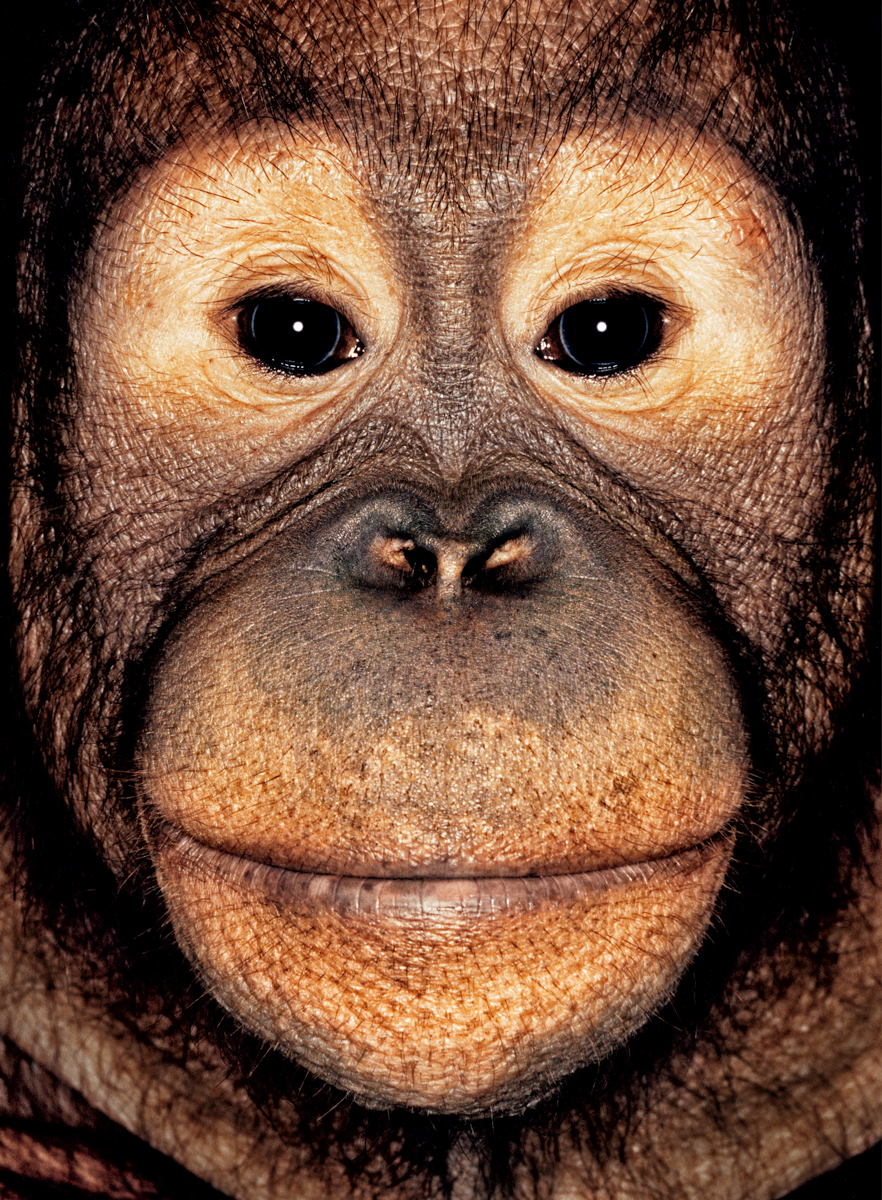

Nearly all of the apes photographed are orphans, except for two of them. For some of them, their parents had been killed for bushmeat. There’s a masculinity belief amongst some groups; they think eating gorilla meat can make you virile.

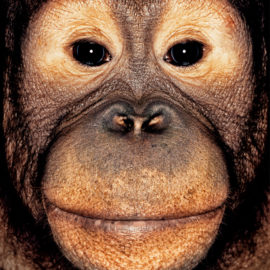

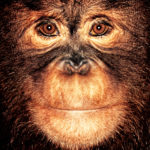

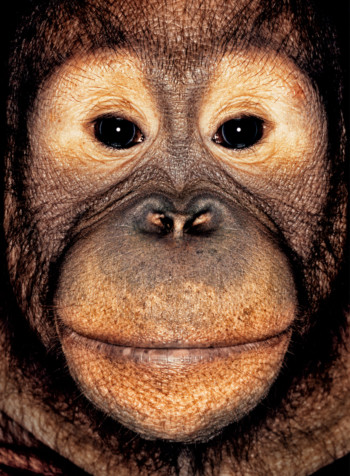

For some of the orangutans I photographed for the project, their parents were killed so they could be taken as pets, but were then rescued.

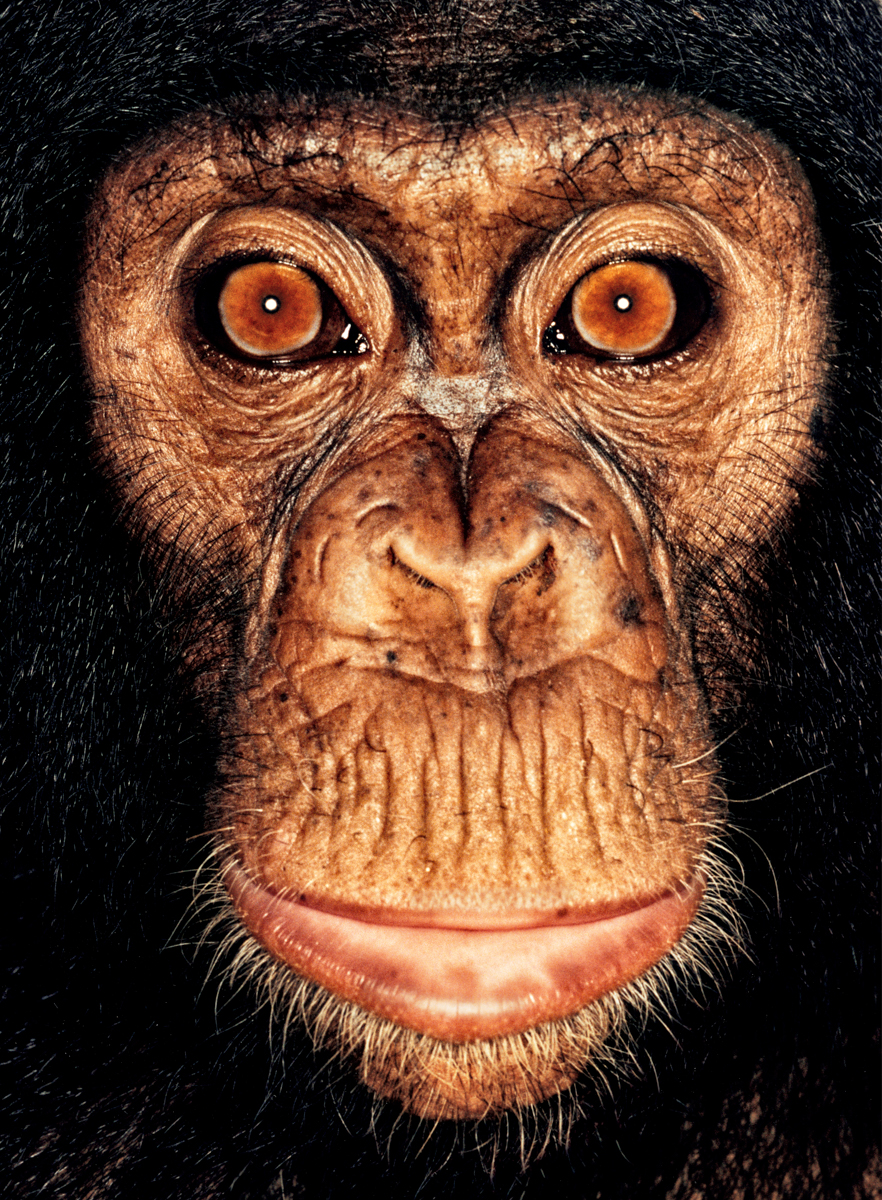

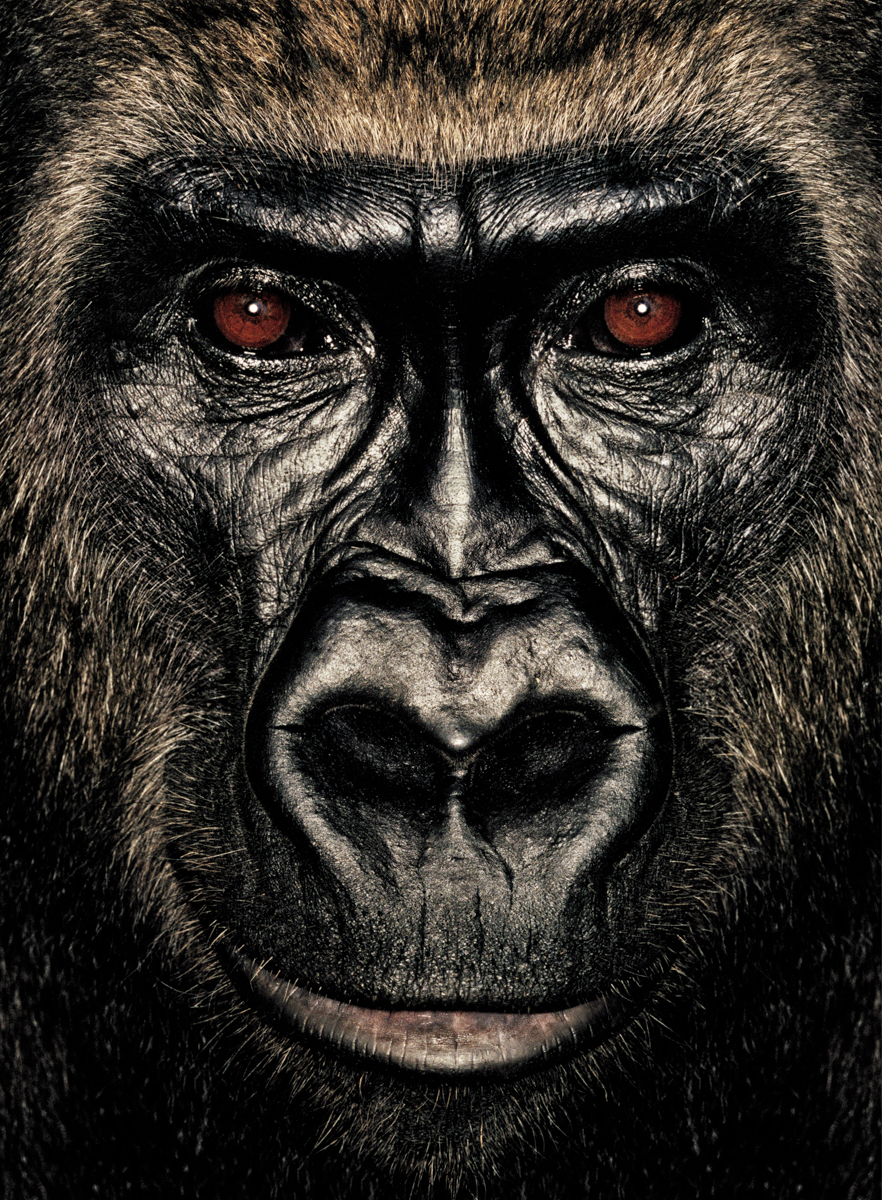

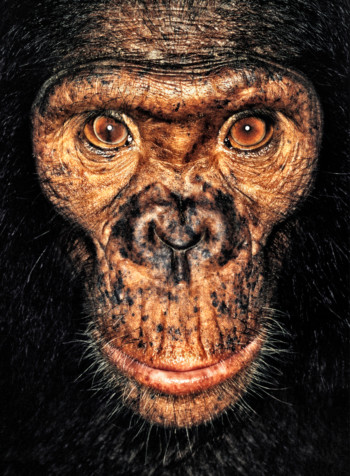

Have you had any reactions to the work which surprised you?

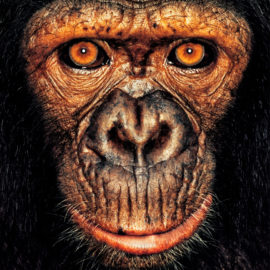

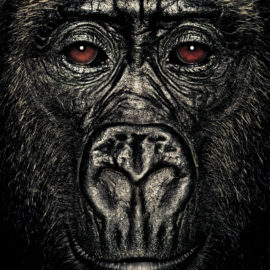

I remember working on another project in the Appalachian Mountains in the American midwest. I was photographing an Evangelical Christian family and remember showing the apes to the mother of the family. It was quite profound for her I think, but it was also quite difficult. Many Americans believe we were created by God. The idea we have evolved from animals is disturbing to them, so it was quite interesting to watch her reaction to the book, and admit that they are so similar to us.

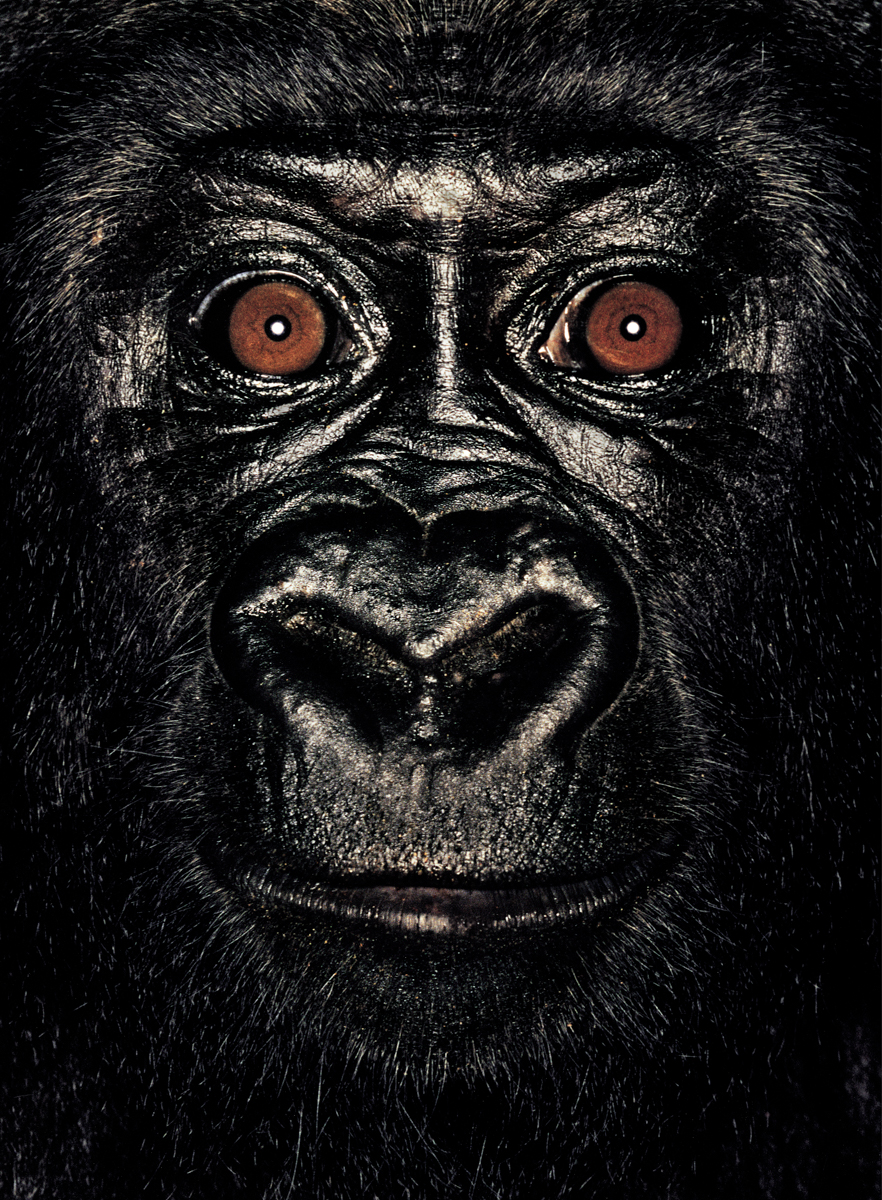

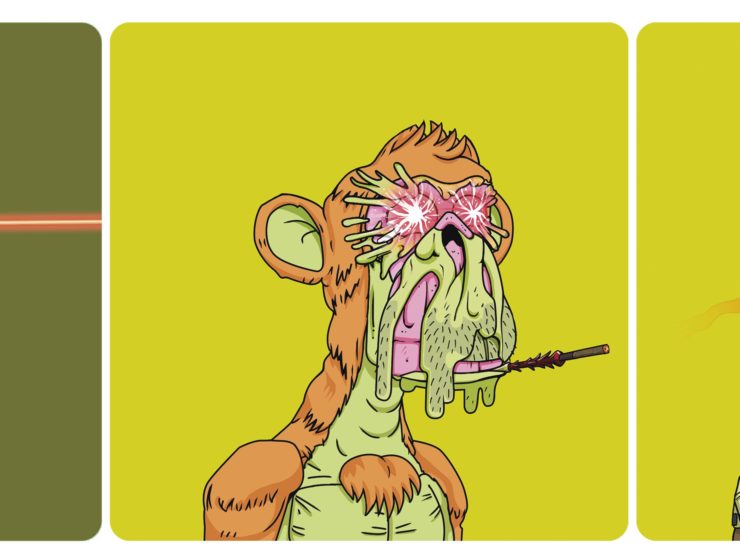

What do you make of the Bored Ape Yacht Club NFT project? it seems to have really captured a lot of people’s imagination.

“I think it’s dangerous to believe we’re far from the animal world. I’ve often seen children look through the project and then look at their own face and say, oh, this ape looks a bit like me. Adults very rarely say that. But I think it’s a good thing to want to identify with an ape and show yourself as an ape. I can understand wanting to express yourself through an ape, because they’re so close to us.”